Housing in Colonial Lenox

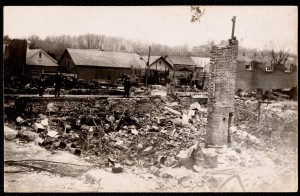

Given the primitive transportation available, housing for the earliest settlers would have been limited to raw materials readily at hand: logs, stone, and clay. Initial houses would have been rudimentary, perhaps with only one room initially with a fire place that would have to double for light, heat and cooking. There may have been a loft for sleeping and generally a dirt floor. Windows, if any, would have been wooden – closing with pegs or rope, or, at best, covered by oil cloth or hides.

-

House Meeting Settlement Guidelines Re-creation in Williamstown, MA - As the children and grandchildren of early settlers of Westfield, Sheffield and western Connecticut, the Lenox settlers would have known what they had to do to make corn meal, hunt for game, find wild berries and herbs, and slaughter and smoke their meat. Their parents or grandparents would have created similar shelters for the first phase of their housing. They probably would have had a treasured metal pot and metal crane for cooking, melting ice, etc.

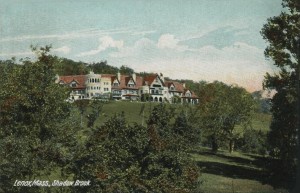

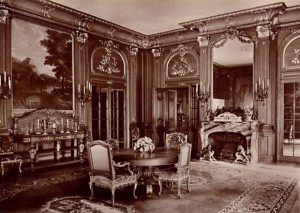

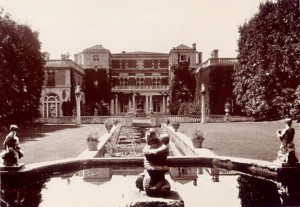

Settlers would upgrade housing, crops and livestock . Settlers would have upgraded to frame houses with stone foundations as soon as quickly as money or more readily available resources permitted. However, the original log house would stand into the 19th century. We can only speculate, but in the increasingly secular and commercial Colonial era, ambitious families were probably as anxious to display their wealth in their homes as they are today.

Wealthier settlers could have accelerated the timing of upgrading (or skipped over the rudimentary shelter phase completely) with the ability to pay for transportation of materials and servants to accelerate the labor of clearing, hauling in goods from the outside and building. The skills to build what we think of as a colonial house would have been readily available and some of Lenox’s proprietors lived in nearby towns where they might have stayed until their new Lenox frame houses were available. Upgrading also would have involved creating shelter for animals and, in many cases, a workshop for the artisan work performed on many farms.

Panelling, cabinets and tables could have been built locally. Pewter, tin and iron housewares (pots, hooks, pitchers, mugs) could have been manufactured by nearby artisans.

Poorer families would have used more wood and clay for utensils and housewares. However, the glassware, windows, china, chairs, bedclothes and tableware we associate with historic Colonial houses would have to have been imported from urban areas and transported in.

Textiles and Clothing

The average housewife would have learned how to make linen (from flax) and wool thread and might have bartered to get it woven in a nearby homestead with access to a loom.

Wealthier households could buy textiles including imported materials such as cotton and silk as well as manufactured items such as metal buttons and buckles. Nearby hatters and tanners could have supplied the average household with jerkins, hats and belts. Dress would have become more elaborate than in the 17th century(although still quite simple by modern standards) and more differentiated by class. The larger landowners, the lawyers and the minister might have sported clothing with manufactured buttons and belt clasps and have worn wigs.

Layers were the order of the day with a ubiquitous undershirt with various levels of outer garments, hats, scarves, collars or ruffles depending on the temperature, the sex and the class. Children would have been dressed as miniature adults.

Colonial Era Economy

As soon as they were able, households would generally have at least one cow, sheep, a pig and some geese or chickens. If farmers didn’t have a team of oxen they would trade services to use a neighbor’s team. Some farmers would have a cart or a horse – but horses were still somewhat of a luxury.

Households without servants to help with the planting, clearing and household work would have sought help from immediate family, gather extended kin or barter for help from neighbors. Either through exchange or cash from market days, any surplus of cheese from cows, eggs from hens, or smoked meat might have been exchanged for help in plowing and harvesting or for tools, tin mugs, woven homespun wool and linen, shoes, cured hides, nails or andirons – etc. – items that other farmers might be making at home for exchange.

Most homes would acquire the ability to make tallow candles and spins yarn. Money as we know it would still have been in short supply and to the degree it could be obtained would have been used to buy land, pay taxes, or purchase goods manufactured or harvested elsewhere including glass, fabric, guns, books, paper, salt, tobacco or tea.

-

The Farmer’s Wife Would Have a Garden for Her Home and for Market If Possible Food choices would have expanded from early days but still would have been primarily what could be grown and preserved locally. Nearby mills would have been used to grind corn into meal (later wheat). Apple trees would have been widely planted and, in addition, to eating and baking, apples would have been widely used for cider and vinegar.

- Honey and maple syrup would have been the primary sweeteners – sugar being an imported luxury. Rum and other distilled spirits my not have been made locally at first but were widely available in the region. Tobacco, tea, coffee and cocoa would have been popular but an imported luxury. A key to lifting the family above subsistence level would have been developing goods to barter or sell — a surplus difficult to come by in the hardscrabble growing conditions of the Berkshires.

- A more popular way to have access to manufactured or imported items would be to have a side trade – often practiced in the farmhouse or in a side shed that could be sold for cash. Examples might have included: tin work, shoe making, leather smith, or blacksmithing. Many homes would have acquired a spinning wheel but not all would have looms to weave yarn into cloth. Work on these side trades probably would have been concentrated during times when the farmer didn’t have to be out planting or harvesting.

- There would have been a handful of what we would, today, call “professionals” – the minister, a lawyer (who would probably have been kept very busy with property changing hands constantly!) and a doctor. The doctor may have been more like an apothecary. It’s highly likely there also would have been a woman accepted as the best at helping in delivery of babies – the midwife.

- Social Life

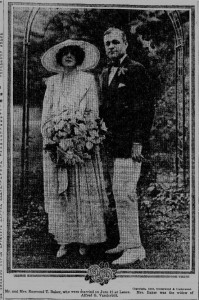

- In addition to Church, there would have been social occasions (probably accompanied by locally distilled malt ale or hard cider) for wedding feasts (not weddings if the Puritan tradition still held), roof raising, market days or militia drill. We have evidence of considerable interaction with other Berkshire communities in the protests culminating in the Revolution–meetings in Pittsfield, Sheffield and correspondence with counterparts in the Connecticut River Valley and Boston. Also, Lenox residents would have had many kinship ties in other Berkshire, Connecticut River and Housatonic River Valley towns. Certainly, with a growing population and improved transportation, Lenox would have been rapidly leaving its isolated frontier status behind by 1775.

- Daily Life in Colonial New England, Claudia Durst Johnson, Greenwood Press, Daily Life History SeriesDaily Life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, George Francis Dow, Arno Press, A New York Times Company, New York, 1977Early Life in Sheffield Berkshire County, Massachusetts, A Portrait of Its Ordinary People from Settlement to 1860, James R. Miller, Sheffield Historical Society 2002The History of Pittsfield 1734-1800, J.E.A. Smith, Lee and Shepherd, 1869History of Lenox, George Tucker ManuscriptEast Street Book, Lenox Historical Society – 1987