On July 14, 1774 one hundred and nine Lenox men made their first official act of rebellion against the British empire by signing an agreement not to buy British manufactured goods.

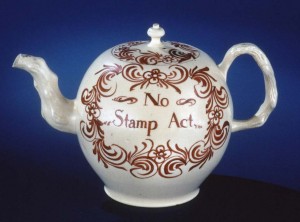

As early as 1764 colonists had been using refusal to buy goods imported from England as a way to avoid paying taxes and tariffs. The first boycott (a more modern term) occurred in response to the Stamp Act. It worked; the Act was repealed. However, Parliament kept trying new ways to collect taxes.

By 1774, lead by John Adams cousin Samuel, committees of correspondence had been organized to coordinate reaction to these waves of Parliamentary attempts to get the American colonists to help pay for the costs of running the empire.

The non-importation agreement signed in Lenox would have been modeled on similar agreements being signed all over the colonies. By this time the committees of correspondence had become (particularly considering 1774 roads and postal services) a surprisingly efficient organization. The agreement would have been discussed at the Berkshire Congress held at about the same time in Stockbridge at the site of the current Red Lion Inn.

There are a number of remarkable things to be said about the Lenox signers.

- To say they had a lot of other things on their minds is a modern understatement. Many of the signers would only have arrived in Lenox only a few years before and would still have been trying to clear enough land to plant and get up a rudimentary shelter. Nonetheless, they probably would have found time to make it to one of the taverns in town (yes – even though there were only a about a hundred households, there were multiple taverns) to have lively debates about taxes and who owed what to whom. Some of these debates would be a continuation of grievances their parents had been accumulating since the end of the French and Indian War.

- Since they were all farmers (even those who had professions or other sources of income)who would have been growing their own food, one might wonder why doing without British imports would make much difference. Although Lenox would have had little currency in circulation and few manufactured goods available for purchase, doing without the British goods that came their way was a genuine sacrifice. Some of the foregone purchases – such as salt, sugar and tea – were easily transported and had few substitutes.

Others such as paint, china, and fabric could have theoretically been made in the colonies, but the British had a monopoly on the manufacturing capabilities and had found it to their advantage to limit the colonies to being providers of raw materials. So again, these few opportunities to improve their lifestyle were realistically available to the colonists only through importation.

Others such as paint, china, and fabric could have theoretically been made in the colonies, but the British had a monopoly on the manufacturing capabilities and had found it to their advantage to limit the colonies to being providers of raw materials. So again, these few opportunities to improve their lifestyle were realistically available to the colonists only through importation. - Finally Lenox (and perhaps all of the Berkshires) must have been at least as inclined to protest as their Boston fellow travelers. The 109 signers probably represented most of the households in Lenox at the time. By the 1790 census there were still only 181 households in Lenox. Also, the signers seem to have had the courage of their convictions since, by one estimate, 55 of them show up on military rolls for the Revolutionary War. It is also noteworthy that leading citizens were willing (a la the national founding fathers) to put their hard won gains on the line – nine of the signers were original proprietors or holders of county grants.

We can only speculate– but perhaps just because they were still wrapped in the struggle to wrestle a living from what was still really wilderness, the thought of losing their property to taxation of courts ruled by royal judges was felt even painfully. Or perhaps (many of these signers would have moved west by 1790), they were thinking ahead (and looking around at the last of the open land in Massachusetts) and were particularly concerned about the 1763 treaty that closed the Ohio frontier to settlement.

For more information see:

Original Non-Importatiaon Agreement available at the Lenox Library

Lenox Massachusetts Shiretown, David H. Wood, 1969

Non-Importation Agreements, Wikipedia, June 2014

George Tucker manuscript (unpublished but available at Lenox Library and Lenox Historical Society)

A People’s History of the American Revolution, How Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence, Ray Raphael, The New Press, 2001

The Marketplace of Revolution, How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence, T.H. Breen, Oxford University Press 2004