What was the end of the Revolutionary War like in Lenox?

This is another instance where we’ll have to guess from information about the general state of affairs.

Major Fighting Ended in 1781 – Surrender at Yorktown

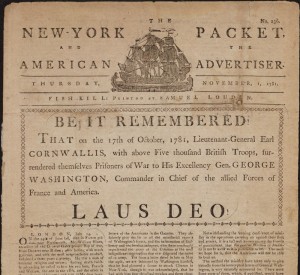

The surrender at Yorktown, October 19, 1781, was not the end of the war, but was the beginning of the end. There’s no reason to think Lenox residents wouldn’t have heard of the victory fairly quickly (by 18th century standards) and have been inclined to lift a glass in celebration.

Lenoxites probably would have known of the arrival of the French fleet and would have been waiting for a major “make or break” military event such as Yorktown

What Would Life Have Been Like During the Late War Years?

After the victory at Saratoga (British General Burgoyne surrendered October 17, 1777), much of the fighting had moved to New Jersey, Pennsylvania and further south. Local militia volunteers likely would have returned to their farms.

The Hudson Highlands and Westchester remained somewhat of a “no-man’s” land with some Tory sympathy but mostly just lawlessness and was the primary location of Gen. Paterson, Joseph Plum Martin and probably the bulk of the Massachusetts soldiers of the Continental Army for the later years of the Revolutionary War.

Would the Continental Army have reached as far afield as the Berkshires to provision the soldiers stationed in New York, Connecticut and New Jersey? Maybe, but the army was penniless, so one could guess that the locals got pretty good at hiding provisions and livestock.

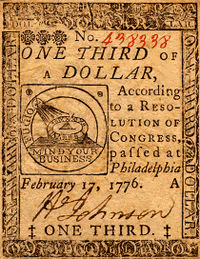

Joseph Plum Martin describes getting his first and only wages in the form of 1200 Continental Dollars on the way to Yorktown. It was only enough to buy a quart of rum! In other words, inflation would have rendered any currency in general circulation more or less worthless. Fortunately, Berkshire County was still largely an agrarian, barter economy.

Joseph Plum Martin describes getting his first and only wages in the form of 1200 Continental Dollars on the way to Yorktown. It was only enough to buy a quart of rum! In other words, inflation would have rendered any currency in general circulation more or less worthless. Fortunately, Berkshire County was still largely an agrarian, barter economy.

Other hardships of war? At the beginning of the war, smallpox was a scourge, but by the end, inoculation was commonplace. Joseph Plum Martin reports numerous outbreaks of influenza and even yellow fever. Fortunately, Lenox probably had some military returnees but a limited concentration to carry these virulent diseases.

Both Paterson and Joseph Plum Martin report the winter of 1779 -1780 as the worst they could remember and meteorological history bears this out.

Rule of law? It’s not clear who was in charge of what, but, other than settlement of international trade, one can imagine that property and criminal law puttered along fairly smoothly. After all, New England towns and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had been governing themselves for some time. In 1780 Massachusetts ratified a new state constitution written largely by John Adams and a model for the 1787 US Constitution.

Although the war probably stalled major investment – and certainly westward movement – local farmers probably continued to improve their landholdings and shelter through promissory notes and or barter.

From Yorktown to 1783 Peace of Paris

One can guess, even in the absence of Pew Polls, that after eight years the population was sick and tired of war. George Washington struggled to hold the starving and unpaid Continental Army together during the tedious two years after Yorktown.

Joseph Plum Martin describes the constant rumors of peace and General Paterson continued to lobby for clothes and food for his troops. Conditions were bad and abetted by boredom and impatience. With his troops wintering in Windsor, NY (near Newburgh), George Washington faced down an officer’s revolt with that bell ringer speech including pulling out his new spectacles and saying,”Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.”

Joseph Plum Martin describes the constant rumors of peace and General Paterson continued to lobby for clothes and food for his troops. Conditions were bad and abetted by boredom and impatience. With his troops wintering in Windsor, NY (near Newburgh), George Washington faced down an officer’s revolt with that bell ringer speech including pulling out his new spectacles and saying,”Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.”

The incident was so moving that many of his officers wept, remembering how much Washington had endured alongside them.

Washington also killed some time during the wait for the peace settlement by inventing the Purple Heart. Strangely it was pretty much ignored after the Revolutionary War until 1932 (lobbied for by that famous publicist Douglas MacArthur).

The new Whig British government was, fortunately, also anxious to end the War. The British also cleverly realized that granted the fervent American wish for western lands would give them a great source of trade that somebody else had to maintain against Indians and other potential enemies.

The regular soldiers who had fought under severe hardship, would come home with worthless promissory notes and impoverished families–at least part of the reason for Western Massachusetts’ Shays Rebellion which was to follow.