Repression in Response to Desperation

The farmers of rural Massachusetts had been struggling with debt and the non-responsiveness of their representatives since before the end of the Revolutionary War. By 1786 protests were escalating. Regulators, as they called themselves, closed the Berkshire County court twice in the fall of 1786.

As many as 9,000 farmers across Massachusetts were eventually involved in protesting the debt collection of the merchants and the courts. Local militia were largely farmers themselves and sympathetic to the Regulators. The commercially oriented elite asked Henry Knox to form (and funded) an army to protect their interests and supplement the local militia. Knox demurred but Revolutionary War veteran Benjamin Lincoln took up the cause.

Aping their pre Revolutionary British predecessors, the Boston dominated legislature passed laws in the fall of 1786 that legalized severe punishment of crowds gathered to protest or riot. Finally in November 1786 they suspended habeas corpus (enabling them to apprehend and imprison protestors for an indefinite period of time without bail). It authorized the arrest and incarceration of anyone suspected of being unfriendly to the government. Further, they passed a bill preventing the spread of false reports criticizing the government.

In an attempt to break up the Shaysites, the legislature further offered an opportunity to be awarded total indemnity if they took an oath of allegiance to the government.

The threat of both force and legal action (without addressing the debt problems at the root of the protest) gained little ground with the Regulators.

From Protest to Rebellion

Many Shaysites (including key figures such as Daniel Shays, Luke Day and Reuben Dickinson) had military experience. They knew (whether government loyal militia or paid army from Boston)troops were coming to quell further action. They needed weapons. The largest weapons cache in New England was in the Springfield Armory.

In January 1787, the Shaysites attacked the Springfield Armory. It was successfully defended by Revolutionary War veteran William Shepard.

Meanwhile Benjamin Lincoln, the failed defender of Charleston during the Revolution, was hard on the heels of the rebels with an army funded and armed by Boston. The Regulators fled first to their home area – Pelham – and then north to Vermont and west to the Berkshires breaking up into smaller groups.

Meanwhile Back in Berkshire County

Major General John Paterson was the leader of the Berkshire militia and a champion of conservative interests in the Pittsfield and Lenox conventions of 1782-1786.

The Shaysites had, by the time they reached Berkshire County, dwindled to 300-400 dispersed and poorly armed men but still seemed to have engendered enough sympathy with the population and members of the militia to alarm Paterson.

“Stockbridge, January 31, 1787

To General Lincoln:

Sir: The desperation of the factions in the County against Government has induced a kind of frenzy, the effects of which have been a most industrious propagation of falsehood and misrepresentation of facts, and the consequent agitation of the minds of the deluded multitude.

Last night, by express from several parts of the County, I am informed of insurrections taking place. My only security under present circumstances will be attempting to prevent a junction o the insurgents, which probably cannot be effected without the effusion of blood; to extricate me from this disagreeable situation, therefore, I pray you, Sir, to send to my aid a sufficient free to prevent the necessity of adopting that measure.” (Egleston p. 186)

By late February, Benjamin Lincoln was in Pittsfield but he had released the militia. His force had dwindled to 30 men.

In fact the “revolution” may have started to disintegrate into a general breakdown of law and order among increasingly disheartened Regulators. Several stories that have been preserved paint the picture.

Just before Benjamin Lincoln reached Pittsfield 250 rebels,under Peter Wilcox, Jr. collected at Lee to once again block the court. Paterson and 300 militia came out to oppose them. The rebels took cover on Perry Hill and got a yard beam from Mrs. Perry’s loom and rigged it to look like a canon. Paterson’s men beat a retreat.

During the same 1787 winter, rebels under Captain Perez Hamlin (from Lenox but residing in New York at the time) Massachusetts and attempted to pillage, among other things, the home of leading conservative – Theodore Sedgwick. The famous Mum Bet hid the family silver and became, once again, a great heroine.

Shortly thereafter Hamlin and his men imprisoned 32 men including Elisha Williams and Henry Hopkins. With these prisoners and their booty they proceeded in to Great Barrington and then, in sleighs on towards Sheffield.

The End of the Insurgency and the Consequences

They were pursued by Ingersoll and Goodrich from Great Barrington, Colonel Ashley of Sheffield and later William Walker of Lenox. It seems to have been something like 100 men on each side but the records are somewhat contradictory. They skirmished across modern-day Sheffield and Egremont. The dead included Solomon Glezen who had been taken prisoner in Stockbridge and allegedly used as a human shield.

The prisoners exceeded the capacity of the Great Barrington jail and the overflow was taken to Lenox. Most were granted pardons.

Most of the Regulator leaders had fled to New York or Vermont so the Berkshire courts were somewhat hard pressed to find an appropriate number of rebels to punish. Two were broken out of the Great Barrington jail by their wives Molly Wilcox and Abigail Austin (really – smuggled saws and everything).

Two, John Bly and Charles Rose, were hung in Lenox (apparently as of Fall 1787 taking its place as the legal center of the County). Richards (p. 41) suspects they were guilty of not much more than breaking and entering in an atmosphere of lawlessness but had few connections so took a fall that many others avoided.

Judge Whiting, who had sympathized with the rebels in the 1786 protests at the Great Barrington courts, was savaged by strong Federalist Theodore Sedgwick. It is likely other sympathizers in positions of authority met the same exclusionary fate.

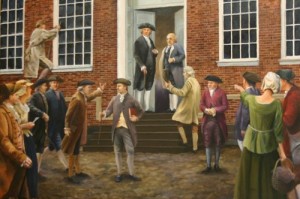

As everyone knows, Shays Rebellion supported the arguments of men like James Madison, George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton that the loose confederation that had won the war against Great Britain, needed to be strengthened. Needless to say, Thomas Jefferson, then Ambassador to France disagreed.

A May 1787 meeting of the Continental Congress had been called and was held before the raid on the Springfield Armory in January 1787. Many delegates decided to come after hearing of the1786-1787 uprisings in Massachusetts.

The resulting US Constitution now included provisions such as creation of a national army that could suppress revolt. Who knows what would have happened to the Constitution sent to the states in September 1787 if the state legislators had not been worried (perhaps unduly) about falling into chaos – the perceived outcome if the Regulators succeeded.

*********

The Life of John Paterson: Major General In The Revolutionary Army, by Thomas Egleston, G.P Putnam’s Sons, New York, NY, 1894

Shays’ Rebellion and the Constitution in American History, by Mary E. Hull, Onslow Publishers, Inc., Berkley Heights, NJ, 2000

Shay’s Rebellion The American Revolution’s Final Battle, by Leonard L. Richards, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, 2002

Shays’ Rebellion The Making of an Agrarian Insurrection, by David P. Szatmary, The University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA, 1980