Western Massachusetts was ground zero for Shays’ Rebellion (1786-1788). Lenox people and institutions were part of the action.

Not Just Shays; Not Revolution

The way most of us heard it, the revolution after the Revolution accelerated the creation of a new Constitution and the tilt toward a strong central government. This “revolution” had something for all future historians to look back on: rural vs. city, wealthy conservatives vs. debt ridden farmers, hard vs. soft currency, and distant government high-handedly ignoring the demands of its citizens.

However, the history of this “revolution” has fostered several long lived misconceptions.

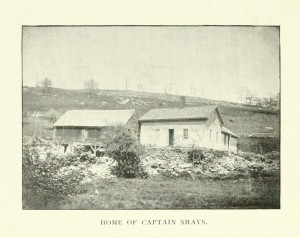

- Daniel Shays was one of several leaders of a largely spontaneous revolt; it is not clear why his name is attached to the uprising. The participants frequently called themselves Regulators after a pre-Revolutionary revolt in the Carolinas.

- “Revolution” is a misnomer in two ways: (a)the protagonists were not shirtless rabble (most owned their own farms) nor did they abandon rule of law (until it seemed they had no choice), (b)there was a great deal of fear and military preparedness on the part of government conservatives but really only one encounter that could be called a battle.

There is even a case to be made that the triumph of the conservative Boston merchants in this interchange- and the soon to be Federalist central government – was almost a counter revolution. Not surprisingly, the symbol for the Shaysites was a sprig of evergreen — the traditional symbol of liberty and independence for Massachusetts flags and coins.

Reasons for Shays’ Rebellion

A review of some of the literature on the topic* indicates the reasons include the following.

-We, as a new and only loosely organized nation hadn’t learned how to respond to citizens’ concerns through legislation – and had only limited infrastructure to do so. Official courts were just beginning to be re-convened.

-The loss of breadwinners (both temporary and permanent), inflation, and lack of military pay had worked tremendous hardship on rural communities that had actively supported the Revolution.

-To make things even worse, as trade picked up, the need for cash increased. The subsistence farmers of western Massachusetts were still a long way from operating on a cash basis and what cash there was was largely worthless paper currency issued by the Continental Congress or state government during the Revolution War. Collection of hard currency debt by (mostly Boston) merchants (who had to supply hard currency to trade abroad) accelerated and rippled through a country side severely short on cash and long on debt.

-Objections were raised not only to the fact of debt collection but to the manner of collection. Typically, in what was still largely a barter economy of farmers producing most of their goods for consumption or local exchange, collection was highly negotiable as to what was collected (e.g. not always hard currency) and how quickly.

-Well, there had been a Revolution, so the notion of protesting what seemed unfair, had become plausible. The infallibility of distant (whether London or Boston) “betters” was less accepted than it had been before the Revolution.

Protests Started with Actions Against Debt Collection

As early as 1782 (prior to the official end of the war), citizens were raising issues via town meetings and protests to local officials about the uncustomary abruptness in debt collection. Increasingly town meetings, state government representatives and county conventions were petitioned to ask for the use of paper current, suspension of debt collection or at least return to practices more consistent with past agrarian custom.

In February 1782, a mob of three hundred tried to obstruct the proceedings of the Court of Common Pleas in Pittsfield (Berkshire County court met in Pittsfield and Great Barrington until Lenox was selected as the county seat.). Later that year, Berkshire County farmers stopped the repossession of a team of oxen for debt. It was just the beginning.

Action and Reaction

By 1786 farmers were at the end of their rope and the protests started becoming more militant. Almost 1500 stopped the Court of Common Pleas on August 29, 1786 in Northampton. Similar actions took place elsewhere in Massachusetts including 800 Berkshire Regulators who closed down the court in Great Barrington in September (Lenox had been named the new location for court in 1782 but court sessions were still in Great Barrington). The cause directly cited was retailers seeking immediate payment in specie.

The protestors locked up the judges until three (Whiting, Barker and Goodrich meeting at Whiting’s house) signed an agreement that they would not meet until revisions had been made to the state constitution.

The Great Barrington protest was a case of history repeating itself, since these Great Barrington courts had been closed in 1774 in protest of judges appointed by the royal government in Boston…effectively starting the Revolution in the Berkshires.

Soon to be Federalist and Revolutionary War hero, Major General John Paterson, spoke up for patience and non-violence in a Lenox convention in August and led the state militia to protect the courts in September. Paterson decidedly represented the conservative faction and it is (Szatmary, p. 81) reported that when he marched into Great Barrington many of those in his militia forces refused to fight their protesting comrades.

Other leaders of the pro government faction included names that continued to appear in the early Federalist history of Lenox and Berkshire County:

Theodore Sedgewick

Joshua Danforth

Simeon Learned

Erastus Sargeant

Ebenezer Williams

Azairah Egleston

William Walker

Caleb Hyde

David Ingersoll

Protests continued and in early October over 200 Regulators again closed the court in Berkshire County.

The rebellion had no formal organization but that was of limited importance since most of the actions were taken by close-knit neighbors and kin. In Berkshire County, the Looses, Nobles and Dodges of Egremont helped stop the court in Great Barrington joined by Issac Van Burgh and his son Issac, Jr., brothers Enoch and Stephen Meachum, and Moses Hubbard an his three sons of Sheffield. The Loveland and Morse families of Tyringham also sided with the Shaysites (Shay’s Rebellion, David Szatmary, p. 62).

*******

The Life of John Paterson: Major General In The Revolutionary Army, by Thomas Egleston, G.P Putnam’s Sons, New York, NY, 1894

Shays’ Rebellion and the Constitution in American History, by Mary E. Hull, Onslow Publishers, Inc., Berkley Heights, NJ, 2000

Shay’s Rebellion The American Revolution’s Final Battle, by Leonard L. Richards, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, 2002

Shays’ Rebellion The Making of an Agrarian Insurrection, by David P. Szatmary, The University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA, 1980

–