We know of no eye-witness accounts of Revolutionary War service by Lenox enlisted men. However, Joseph Plumb Martin from Becket gives a fascinating and colorful picture of what life would have been like for all the brave and long suffering ordinary soldiers of the Revolution. Joseph Plumb Martin wrote of his experiences in “Ordinary Courage.”

Why and How Joseph Enlisted

Joseph, working on his grandfather’s farm, explains how he came to enlist:

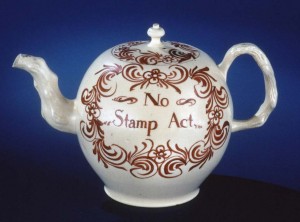

“I remember the stir in the country occasioned by the Stamp Act, but I was so young that I did not understand the meaning of it; I likewise remember the disturbances that followed the repeal of the Stamp Act until the destruction of the tea at Boston and elsewhere. I was then 13 or 14 years old and began to understand something of the works going on. I used to inquire a deal about the French War, as it was called, which had not been long ended; my grandsire would talk with me about it while working in the field…” (Ch. 1)

In the same chapter he describes the sense of local tension and alarm:

“I was ploughing in the field about half a mile from home (which would have been Connecticut – where his grandfather lived), about the 21st day of April (1775) when all of a sudden the bells fell to dinning and three guns were repeatedly fired in succession down in the village….The regulars are coming in good earnest, thought I.”

At first, Joseph has no interest in enlisting but then:

“This year there were troops raised both for Boston and New York. Some from the back towns were billeted at my gransire’s; their company and conversation began to warm my courage to such a degree that I resolved at all events to ‘to a sogering'”

However, his grandfather did not give him permission to enlist (he would have been only 15) and:

“Many of my young associates were with them; my heart and soul went with them, but my mortal part must stay behind. By and by they will come swaggering back, thought I, and tell me of all their exploits….”

In July 1776 Joseph got his wish when his town was required to provide enlistees for the defense of New York. Upon being told that the British had been reinforced by 15,000 men he reports, “I never spent a thought about numbers; the Americans were invincible in my opinion….”

Joseph’s Account of the Kip’s Bay ‘Affair’ and the Retreat from New York

Joseph has a laconic story telling style that would become classic yankee. He speaks of battle as things getting “warm,” and constantly makes sarcastic comments about food (and was probably hungry almost all the time.) Although many of his stories of duty in Westchester and New Jersey tell of indifferent patriots or tories, here he paints a picture of interactions between both friends and foes while on the march:

“I found myself in company with one who was a neighbor of mine when at home and one other man belonging to our regiment; where the rest of them were I knew not. We went into a house by the highway in which were two women and some small children, all crying most bitterly. We asked the women if they had any spirits in the house; they placed a case bottle of rum upon the table and bid us help ourselves. We each of us drank a glass and bidding them good-bye betook ourselves to the highway again. We had not gond far before we saw a party of men apparently hurrying on in the same direction with ourselves. We endeavored hard to overtake them, but on approaching them we found they were not of our way of thinking; they were Hessians.” (Chap. 2)

And in this retreat he tells (as he will in all the future campaigns) of the inadequacy of rest and food:

“I still kept the sick man’s musket; I was unwilling to leave it, for it was his own property, and I knew he valued it highly, and I had a great esteem for him. I had enough to do to take care of my own concerns: it was exceeding hot weather, and I was faint, having slept but very little the preceding night, nor had I eaten a mouthful of victuals for more than 24 hours.”

And he gives a personal account of the hopes of the enslaved to be freed by serving with King George:

“The man of the house where I was quartered had a smart-looking Negro man, a great politician. I chanced one day to go into the barn where he was threshing. He quickly began to upbraid me with my opposition to the British. The king of England was a very powerful prince, he said–a very power prince; and it was a pity that the colonists had fallen out with him; but as we had, we must abide by the consequences. I had no inclination to waste the shafts of my rhetoric upon a Negro slave. I concluded he had heard his betters say so. As the old cock crows, so crows the young one; and I though, as the white cock crows, so cross the black oe. He ran away from his master before I left there and went to Long Island to assist King George; but it seems the King of Terrors was more potent than King George, for his master had certain intelligence that poor Cuff was laid flat on his back.”

(This may refer to death by small pox which was rampant — particularly among the former slaves who enlisted with the British troops.)

Why Joseph Re-Enlisted for the Duration of the War

By 1777 the rage militare of 1775 had all but disappeared. It was now apparent the war would be a prolonged affair and that the ‘sogering’ Joseph had looked forward to was more hunger and exhaustion than glory.

Nonetheless, like soldiers throughout history, Joseph re-enlisted because his friends did — and perhaps we can speculate–because he was young and wasn’t sure what else to do.

The Suffering of the Continental Army

(From Chapter 3)

“One of my mates, and my most familiar associate who had been out ever since the war commenced, and who had been with me the last campaign, had enlisted for the term of the war in the capacity of sergeant. He had enlisting orders, and was every time he saw me, which was often, harassing me with temptations to engage in the service again. At length he so far overcame my resolution as to get me into the scrape again, although it was at this time against my inclination, for I had not fully determined with myself, that if I did engage again, into what corps I should enter. But I would here just inform the reader, that that little insignificant monosyllable–No–was the hardest word in the language for me to pronounce, especially when solicited to do a thing which was in the least degree indifferent to me; I could say Yes, with half the trouble.”

And he gives us an account of the army’s war on smallpox:

“….with about 400 others of the Connecticut forces, to a set of old barracks a mile or two distant in the Highland to be inoculated with the smallpox. We arrived at and cleaned out the barracks, and after two or three days received the infection….I had the smallpox favorably as did the rest, generally.”

And he describes the growing hardship of his squad:

“Their whole time is spent in marches (especially night marches) watching, starving, and in cold weather freezing and sickness. If they get any chance to rest, it must be in the woods or fields, under the side of a fence, in an orchard or in any other place but a comfortable one, lying down on the cold and often wet ground, and perhaps, before the eyes can be closed with a moment’s sleep, alarmed and compelled to stand under arms an hour or two, or to receive an attack from the enemy; and when permitted again to endeavor to rest, called upon immediately to remove some four or five miles to seek some other place, to go through the same maneuvering as before; for it was dangerous to remain any length of time in one place for fear of being informed of by some tory inhabitant (for there were plenty of this sort of savage beast during the Revolutionary War.)…..”

He recounts more on the lack of provisions:

“In the cold month of November without provisions, without clothing, not a scrap of either shoes or stockings to my feet or legs, and in this condition to endure a siege in such a place as that was appalling in the highest degree.”

Joseph’s suffering goes on throughout the war – and often in situations where surrounded by plenty. He rightly resents the lack of sacrifice of the civilians who claimed to be patriots.

It is interesting to note that there was no such thing as an “American” yet. Joseph refers to the Pennsylvanians as foreigners.

Peace and Prosperity – Not

When the war ended in 1783 Joseph was still only 22 years old. He had had little education and is grandfather’s farm was gone. After a brief stint teaching school among the Dutch settlers in the Hudson Highlands, he made for Maine in response to rumors that land was available on easy terms. Like most of the common soldiers of the Revolutionary War, he mustered out with little except whatever tattered clothes he had on his back.

Settling near the mouth of the Penobscot River, he married, had children and lived another 66 years. He was apparently well thought of by his fellow townsmen — elected to the board of selectmen seven times. However, he never prospered and, like many veterans of the war, received scant reward for his service. In 1797 he finally received title to 100 acres of land in the Ohio territory, but he was already in Maine and owed for the land he had settle on there. His bounty land was assigned to a land agent for whatever cash could be raised.

See:

Ordinary Courage, The Revolutionary War Adventures of Joseph Plumb Martin, Fourth Edition, Edited by James Kirby Martin, Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2013 (e edition)