Settlement of the Berkshires – Poontoosuck

Of the five Berkshire towns whose settlement have are briefly covered in these blogs(Sheffield, Stockbridge, Great Barrington, Poontoosuck* and Lenox), Poontoosuck (Pittsfield) suffered the most from the continuing conflict between New England settlers and the French and their Indian allies.

In 1722, 177 men from Hampshire County sought a grant for the “Valley of the Hoosatonuk,” or “Westbrook.” By 1735 Boston was seeking proprietors for 3-4 townships to

-generate income for the Boston poor and free schools

-establish settlement in the area recently disputed with New York

-populate the area with Massachusetts men (and women) who could protect the colony from future invasions from New France (Canada.)

Col. Jacob Wendall purchased the 24,000 acres that would become Pittsfield for about 2100 pounds. He partnered with Phillip Livingston of New York and Capt. John Stoddard of Northampton who had already been given 1000 acres in return for his military service. Livingston had thought to sell parcels to 60 Dutch families there from New York to meet the settlement requirements. The New Yorkers were not that interested plus someone got around to read the fine print of the grant and realized the settlers had to be from Massachusetts.

Finally, in 1743, 40 young men had been assembled who were ready, willing and able to take their chances in return for cheap land in this frontier area and clearing began. Unfortuntely, war broke out again in 1744 (King George’s War/ War of the Austrian Succession) and clearing and building was largely abandoned. Many of these men would have been back and forth for general militia duty or defense of Fort Massachusetts (near modern day Adams).

With peace, many of these hopefuls returned along with additional purchasers, and by 1752 some temporary log cabins were built. The first settlers, Solomon Deming and his wife Sarah travelled through the woods clearing a path as they went. They came from Wethersfield and others from Connecticut and Northampton followed. By 1753 things were looking promising enough that a petition was presented to the general court for township status (which would have provided for collection of taxes for roads, meeting house, etc.) Good progress had been made with most of the 60 proprietor lots taken up and population had climbed to around 200. However progress was again halted by war.

The Flight from Poontoosuck and Lenox to Stockbridge

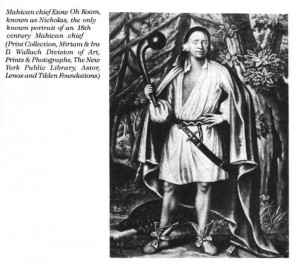

Although the concentrated Indian population of the Berkshires (about 300 Stockbridge Indians) remained peaceful, several Indians wondering through the Berkshires and angered by the death of a family member in a horse theft incident touched off a new wave of fear of Indian attack. This was followed in short order by a new French and Indian War in 1756.

Based on the initial Indian violence in 1753, Berkshire County sent for reinforcements. With the help of horses from Connecticut, Poontoosuck evacuated to Stockbridge in haste. The refugees were fired on as they fled south and one man (Stevens or Stearn) was killed. The woman riding with him was rescued by Jonathan Hinsdale of Lenox.

Developing Property vs. Serving in the Militia

Settlers tried to return to protect, and if possible, cultivate their properties. Many of the men would have been in the militia defending Fort Massachusetts (near Adams), Fort Anson in Poontusuck, or to participate in the ill-fated attempt to capture Fort Ticonderoga. Poontoosuck would have been a stopping place for troops from the rest of New England on their way to Canada or Fort Royal and some would return as settlers.

Settlement Began in Earnest in 1759

With Wolfe’s capture of Quebec in 1759 settlers started returning in earnest. In 1761 Poontusuck was granted the right to incorporate and the name Pittsfield was chosen in honor of Prime Minister William Pitt who had lobbied Parliament to provide military support for the colonists against the French and the Spanish.

*”Poontoosuck” = another phonetic Indian name spelled many different ways. This spelling is taken from the 1752 survey.

See

A History of the County of Berkshire, Massachusetts, by David Dudley Field and Chester Derwey, Pittsfield 1929, “A History of the Town of Pittsfield, ” by Henry Strong

A History of the Town of Pittsfield in Berkshire County, Massachusetts 1734-1800, by J.E.A Smith, Published by The Town of Pittsfield, 1868

Berkshire Creative Website, 2014

Wikipedia, 2014